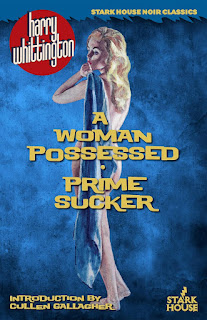

9798886010671

Stark House, 2023

216 pp

It's Booker Prize season, which has nothing at all to do with this section of my reading journal, but I've been reading some pretty heavy hitters lately, and I've taken a few badly-needed brain breaks in between. Crime fiction from yesteryear has been the ticket, and I don't mean country house murders. The author of both tales in this book is Harry Whittington (no, not the guy who Dick Cheney shot in the face back in 2006), and according to the bibliography of his work at the end of this volume, to say that he was a prolific author is an understatement. Sheesh! I gave up counting after a while. There is a brief bio of this writer included in the informative introduction written by Cullen Gallagher; there's also a longer essay that you can read online by Woody Haut at his blog.

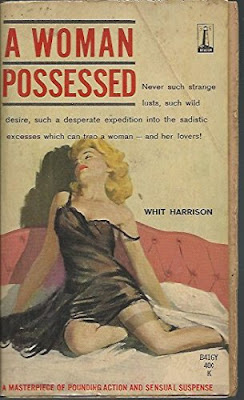

Originally published in 1961, A Woman Possessed was published under one of Whittington's many psedonyms, Whit Harrison. The original cover touts "strange lusts, ... wild desire, ... sadistic excesses," and all of those are definitely included here. When it comes right down to it though, this is a story about revenge, sweet and otherwise.

|

| original 1961 Beacon edition, from Amazon |

Dan Ferrel is working with fellow prisoners in a road gang alongside the highway in the midst of "slash pine and cabbage palmetto country." He's tense -- the blue car that's he's been anxiously awaiting is late. It's the vehicle that's going to take him away from prison and he knows that if his escape doesn't go as planned, "he would never get another chance." It's a huge risk, for sure: Hawkins, one of the guards overseeing the prison crew has "an itch to pull down on his gun and shoot a man... so bad it's killing him." His sadistic impulses are kept in check only by the fact that ten convicts are currently involved in "civil rights trials," testifying about the "inhuman treatment" they'd received from six prison guards and the powers that be given orders for the guards to "Walk easy with these cons." Like Hawkins, Ferrel is also a man with an itch ... as one of his fellow inmates notes, he "ain't got the itch to kill," but "you just got an itch." He really needs to get away because he urgently has to see his brother Paul, who, as rumor has it, is about to quit med school because he'd become involved in "chasing a dame, wrecking his life," and Dan knows all about the woman, most especially that she's bad news. Keeping Paul on the straight and narrow is Dan's raison d'être; Dan may have "fouled up, but Paul was not going to, not as long as Ferell was breathing." Needless to say, there wouldn't much to talk about here without success on Dan's part, at which point the story takes more than a few unexpected turns before heading straight into revenge territory. It's an awesome and action-packed read; as Gallagher describes the book in his introduction, it's "Sweaty, grimy and relentless," and it kept me turning pages. A Woman Posessed is my first foray into the world of Harry Whittington, and despite the often cringeworthy, eye-roll inducing descriptions of sex, I was hooked for the duration.

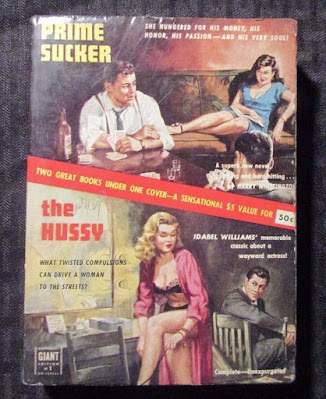

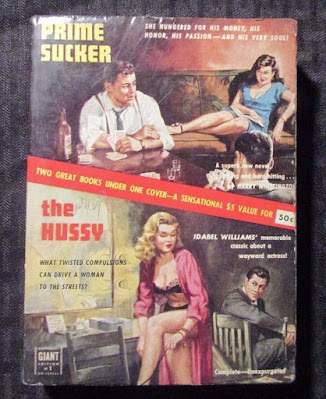

An earlier version of the next novel, Prime Sucker (which Beacon would publish later in 1960) had initially appeared in 1952, paired in a Universal Giant edition along with Idabel Williams' The Hussy from 1933.

|

1952 Universal Giant edition; photo from ebay

|

It seems that in the eight years between 1952 and 1960 (according to the introduction), Beacon's reprint edition had been "spiced-up" as "...publishers could get away with a lot more lurid passages than in 1952 -- and their audience had come to expect as much." It looks like even the cover art for this book became more lurid in the intervening years as well.

Prime Sucker starts with a friendly poker game among work colleagues. The poker game is hosted by George, who works under Hank Ireland at the Thompson Company. The author wastes no time letting his readers know that Hank "wanted George's wife. It was like being drunk, the way she made him feel." He's pretty sure that Amy wants him as well -- that "she wanted whatever he wanted." In fact, he reads in her eyes that she wants "whatever any man wants. Any man." Between the drinks he's downed, the cigarette haze and the lust oozing out from Amy's eyes, he's distracted and woozy, unable to concentrate on the game. Feeling sick, he goes into the kitchen for ice water, followed by Amy whose job all night has been to get drinks for the poker players. He feels sick and knows he should go home, that he needs to get away from her, but instead he kisses her. It's not just any kiss but one that solidifies Hank's feeling that he has to have this woman, and the way she reciprocates lets him know she feels the same way. And while he doesn't realize it, that kiss is about to change his life completely. He does the smart thing and goes home to his wife, and although he gets a cold reception there, he makes up his mind the next day that he will never see Amy again. What he doesn't know is that there are forces at play that conspire to bring the two together. I really can't reveal more about the plot, except that in this story, at least for the first several chapters, nothing is as it seems. It takes a while to get down to the jaw-dropping nuts and bolts of this story, but by that time, Hank is pretty much a lost soul, but a lot of that is his own fault -- he won't even try to save himself, refusing the lifeline time and again.

Of the two books I preferred A Woman Possessed -- the story was a bit more straightforward and there was less melodrama involved, whereas I had to wait a lot longer for the payoff in Prime Sucker. It's also very apparent that both books were written well before #metoo, so reader beware. The sleaze factor is also high between the two novels but I've read way worse so that wasn't a big issue for me, although it was hard sometimes not to cringe; seriously, if the steam coming off these stories had been real I would have had to stop and clean my reading glasses many times. I suppose the big question is whether or not I'd read any more books by this writer and now that I've taken that plunge, "headfirst and deep down into Whittington's world of warped desires" I'm definitely down for more. I can't help myself, really. I love pulp. Great literature it's not, but who cares -- it's so much fun.

Once again, my many thanks to Stark House Press, whose books have introduced me to authors I didn't even know existed and who have provided me with hours of great reading. I've had the privilege to read one of their new books coming out next month, another two-books-in-one edition, this time by another previously-unknown (to me) author, Lionel White: Too Young To Die/The Time of Terror, both of which I sat glued to. I've also just bought two more of their books, short story collections from Robert Hichens, whose work deserves to be brought back into the light.